Author: Garfield Krige (SCE129)

The residents of Sterkfontein Country Estates are rather privileged. Not only do we reside in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, we also have a remarkable variety of, often rare, flora as well as interesting fauna. On top of that, forming part of a karst landscape, our area also boast some of the most spectacular caves in the country. This page is dedicated to introducing you to the wonderworld of our subterranean inheritance.

Click on any of the small pictures to open the full-size photo

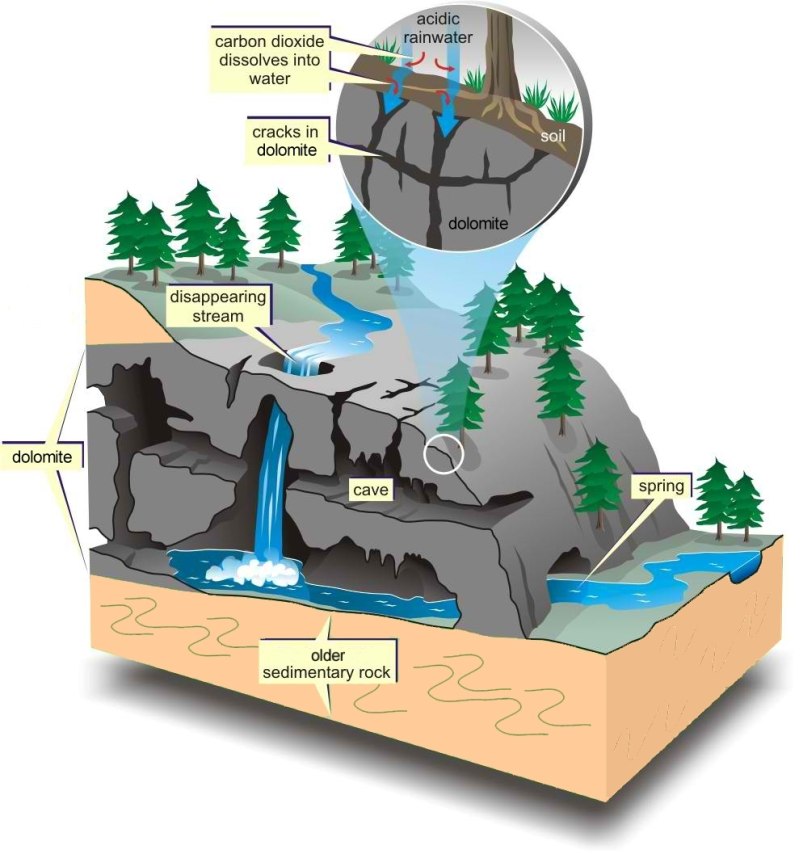

The formation of caves in dolomite

On the web page “The Story of Malmani Road“, we explained how the sedimentary rock, dolomite, on which Sterkfontein Country Estates is located, was formed. In short, Malmani Rd is named after the Malmani Sub-Group of the Chuniespoort Group, Transvaal Supergroup. Dolomite, named after the French Naturalist and Geologist, Déodat Gratet de Dolomieu (1750-1801), is, indeed, a very special type of rock. It was formed as a result of the actions of a group of ancient bacteria, the cyanobacteria, some 2.6 to 2.2 Billion years ago. For more information on where dolomite comes from, it might be worthwhile to first read “The Story of Malmani Road“, before continuing reading this page.

In the second paragraph of “The Story of Malmani Road“, we warn about the potential hazards relating to poor water management, with particular emphasis on French Drains and leaking underground pipes. Also note dolomite is susceptible to the formation of sinkholes and caves.

Over millions of years, the dolomite, just like all the other types of rocks, became fractured due to forces (movement) from within the crust of the earth. These fractures, or cracks, are referred to in geological terms as “faults“. Although dolomite is a pretty solid type of rock, these weaker fault zones in the dolomite provide access for water to penetrate deep into the rock.

Under natural conditions, rainwater is slightly acidic because of the presence of dissolved carbon dioxide. This is the result of rainwater dissolving carbon dioxide from the air through which it falls. Once on the ground, it continues dissolving carbon dioxide from the soil while seeping down to the groundwater.

When carbon dioxide dissolves in water, it forms a weak acid called carbonic acid. As its chemical name, calcium magnesium carbonate, suggests, dolomite is a carbonate-type rock (similar to limestone, just much harder). This means that dolomite is vulnerable to the dissolving power of acidic water. When the slightly acidic water seeps into cracks and fractures in the dolomite, it will dissolve small amounts of rock. Over time, and due to the dissolution of the carbonate rock, these cracks could open up into larger cracks, allowing greater flow and gradually (and under the right conditions), the flow of water will increase and so too will the dissolving of dolomite increase. Eventually, these cracks could turn into caves.

However, due to the rate at which water percolates through the zone above the water table (referred to as the vadose or unsaturated zone), and also as this is a slow process, most rock is dissolved only once the rainwater reaches the groundwater table. Thus, rainwater retains some of its acidity and consequential dissolving power until it reaches the groundwater table. Upon reaching this groundwater zone, the remaining acidity in the rainwater is “used up” at, and just below, the groundwater table, and significant amounts of rock is dissolved in this zone. This is also the reason that caves usually form at, or just below, the groundwater table.

Due to seasonal, and in particular, the continuous climatic changes experienced by our earth, the groundwater table is by no means stable at one elevation. It could rise and fall by several metres seasonally (summer-winter variations) and over longer periods, could rise or fall by several tens or even hundreds of metres. As an example, around 10 000 years ago, our earth was just beginning to come out of the last ice age. During this ice age, the groundwater table across most of our earth was much lower than it is today. Similarly, the sea levels were also several tens or even hundreds of metres lower due to much larger amounts of water being found in the form of ice on land. Even further back in the earth’s (more recent) history, around 40 Million years ago, the earth was almost totally ice-free! This meant that sea levels were at their highest and that groundwater tables on land were also much higher than they are at present. Interestingly, most of the offshore oil deposits found along Africa’s west coast were also formed during this time.

Had the groundwater table not fluctuated, most of the caves would have been the same size. However, because the groundwater level continuously rises and falls, it resulted in caves not necessarily being thin and flat, but occasionally resulted in huge caverns.

Over time this type of landscape will mature and more openings into caves and other underground voids could form. On the odd occasion, it could even lead to underground rivers, where a river disappears into the underground environment only to reappear some distance downstream as a flowing river on the surface of the land. Collectively this type of landscape, formed from the dissolution of soluble rocks such as limestone, dolomite, and gypsum, is referred to as Karst Topography. This type of landscape is characterized by underground drainage systems with sinkholes, dolines, and caves.

From research done by the University of the Witwatersrand at Sterkfontein Caves, a few kilometres east of Sterkfontein Country Estates, it is suggested that the caves in the vicinity of Cradle of Humankind (including SCE) are about 20 Million years old – that’s at least roughly when the process of cave formation began.

Once all the acidity in the rainwater is “used up” by dissolving some of the dolomite rock, the water acquires an alkaline character, as it now contains elevated amounts of calcium and magnesium carbonate in solution. The dissolved carbonate is the building block for cave formations.

Speleothems or Cave Formations

Above it was described that water percolating through the dolomite rocks would dissolve varying amounts of dolomite. The calcium carbonate dissolved in this way is described as being “sparingly soluble” in chemistry terms. This means that a small environmental change (pH, temperature, presence/absence of carbon dioxide, presence/absence of air movement through the cave, presence/absence of other substances in solution, etc.) could be all that is needed to change the calcium carbonate from a solution in water to a solid. Obviously, the rainwater percolating through the dolomite rocks above a cave would be nearly saturated with dissolved calcium carbonate. As this water reaches the air-filled chamber of a cave, the environmental conditions for the dissolved calcium carbonate would be changed ever so slightly. This usually results in the precipitation of calcium carbonate (now referred to as the mineral, calcite) and this is how speleothems are formed.

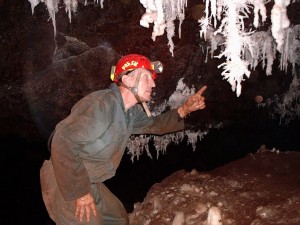

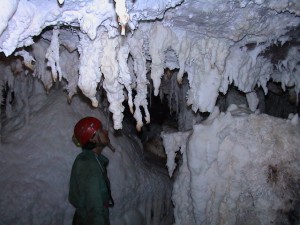

There are many forms of speleothems. The most obvious ones are dripstones (the hanging stalactites and the upright stalagmites). But there are many more types, such as flowstone, helictites, true calcium carbonate or calcium sulphate crystals and many more with less scientific names, such as spurs, rafts, curtains, fishtails, straws, etc. We have even invented our own name for a specific formation, “Bubbles”.

- The photographs directly below serve only to illustrate some of the different cave formations and are not necessarily taken in caves on our Estate.

Cave formations form at a comparatively (but very variable) slow rate. In our area hanging formations are formed at roughly 2.5 cm per century. However, the rate of growth could vary considerably, depending on the environmental conditions present in the cave and in the rocks above the cave.

There are several caves within the boundaries of SCE or in the immediate vicinity of the estate. Virtually all of these caves had been mined during the late 1800s and early 1900s for their calcite and to make cement for the emerging gold mining industry on the Witwatersrand. This is really a pity, as many caves (and particularly their speleothems) had all but been destroyed. On the other hand, had it not been for this mining at Sterkfontein Caves, neither Mrs. Ples nor her family of Australopithecus africanus (early hominids, who lived in the SCE area between about 3.03 and 2.04 million years ago), would probably have been discovered.

Fossils in Caves

Sterkfontein Country Estates falls within part of the greater Bolts Farm area. This area, centred around the actual Bolts Cave, is a zone in the dolomite where particularly many caves are found and where many fossils occur.

The fossils found in caves are not necessarily fossils of animals that lived in the caves, but are often the bone fragments of prey that were brought into the cave by a predator. Sometimes, however, a “whole” animal would fall down a cave entrance and the entire skeleton would become fossilised.

On the subject of fossilisation, it is well known that limestone and dolomite are good environments to preserve bones. This is simply because bone has very similar chemical properties to carbonate and thus would not be eroded by the rocks surrounding the bones. Over time, the material (bones, together with sand, stones, rocks and other material) that fell into the cave shafts built up to form talus cones, which look like giant, inverted ice-cream cones, on the cave floor. These deposits are subsequently cemented into a concrete-like substance, by the lime-rich water to form a type of rock called breccia. Bones within these talus cones are mineralised by calcium carbonate within the breccia.

The two important caves on our Estate are protected against vandalism and are in safe hands, thanks to the conservation consciousness of the landowners Louis Trichardt and André Grové, on which Wind Gat (also known as Virtual Reality), and Knocking Shop Caves are located.

Fortunately, neither of these caves were mined during the gold rush era. When looking at the photographs below, it will become clear that these caves are not suitable for commercial exploitation in any way whatsoever (even if permission could be obtained from the authorities to do so – something virtually impossible!). The caves themselves are just too delicate and both caves’ entrances and passages are too narrow for the “average” tourist.

Furthermore, these caves also happen to be two of the most spectacular caves found in this vicinity, boasting absolutely unique cave formations. Although our caves are not of the huge cavernous type such as Wonder Cave, or to a lesser degree, Sterkfontein Cave, our caves boast the most unique and fragile speleothems imaginable.

So join us in a photographic journey of this subterranean wonder world!

Wind Gat/Virtual Reality Cave

This cave has two different names, depending on whom you talk to.

If you talk to the landowner (Louis) or the author (Garfield), it will be named “Wind Gat” (the Afrikaans for “wind hole”). This name was derived from the strong air movement into and out of the small entrance of the cave. Such air movement suggests that this cave is connected to a large underground void. Most likely, there is still a lot of cave to be explored!

However, members of the Speleological Association of South Africa (SASA) would most likely refer to it as the “Virtual Reality Cave”, simply because it has the most breathtaking cave formations imaginable. Either way, have a look at the photos below. This cave is simply stunning!

All but one of the Wind Gat Cave photographs by Garfield Krige

Knocking Shop Cave

Apparently this cave was named “Knocking Shop” because of all the hammering necessary to breach the initial entrance many years ago when it was first discovered. We heard a very different story, but will stick to this explanation!

Acknowledgements

Dave Ingold (who supplied photos of the Knocking Shop Cave and other assistance regarding caving) of Speleological Exploration Club (www.sec-caving.co.za), a founder member of the South African Speleological Association (SASA); Neil Norquoy of Wild Cave Adventures (www.wildcaves.co.za) who accompanied the author on many of the caving expeditions; Louis Trichardt (a SCE resident) and André Grové, a speleologist (www.caves.co.za)

- About the author: Garfield Krige, a local SCE landowner, was a contributing author of the Water Research Commission publication, ‘The Karst System of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site‘ – WRC Report No. KV241/10 (May 2010).

Download it here (PDF version, file size: 5.67 MB):

The Karst System of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site (KV 214/10).

Additional Information

After reading the above article, those who are now a bit more interested in the caves in the general vicinity of SCE, we suggest reading more about our caves at the websites listed above. One website of particular interest is the Wild Cave Adventures website (www.wildcaves.co.za). Of particular interest to some visitors may be the art of cave photography. The author, Garfield, wrote a short article about the “art” of taking pictures in a cave. Read it here:

http://www.wildcaves.co.za/assets/education/cavephotography.htm.

Please Take Note:

All caves in South Africa are protected by law. This is true for all caves, even those on your own property. You may not disturb, or remove anything from a cave or cavern, unless you have the specific permission from the authorities. This includes the dumping of rubbish into a cave! This is also true for entering a cave. Nobody is allowed to enter or disturb any cave if they are not supervised by, or a member of a specialist speleological body (such as a recognised speleological association or caving club) which does have the necessary permission.